Notes on Cohousing and Coliving

In pursuit of a more perfect union, let me live with my best friends.

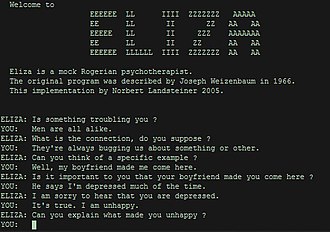

The excellent podcast 99% Invisibile had an episode about Joseph Weizenbaum and his creation: ELIZA, a computer program we would now call a chatbot, developed in the ‘60s. Wikipedia describes it almost like a lark: Weizenbaum created the program “to demonstrate the superficiality of communication between humans and machines.”

He showed it to his secretary and grew unsettled when, after a few interchanges, she asked for some privacy to continue her conversation. He realized she was engaged with the chatbot in a meaningful conversation, almost like one would be with another human or therapist. That the program resembled a therapist is not an accident. Weizenbaum’s innovation was not in the technical depth or sophistication of his chatbot—lookup tables of stupendous quantities of facts and figures, memory dependencies for the entire lengths of conversations instead of merely one exchange, statistical models that mirrored the distribution of observed human speech patterns, etc. It was in his recognition that the most emotionally resonant conversations humans routinely have are those in which the subject is prompted to reflect through a series of rather simple questions. “What do you mean by that?” “Can you explain?” How did that make you feel?”

Weizenbaum’s was unsettled watching his secretary entranced with ELIZA. He felt the violation of a strong intuition that he had—namely, that emotionally resonant conversations, almost by definition, require a human interlocutor. And yet his chatbot was not human. The story with Weizenbaum is that he spent the remainder of his career on an anti-AI campaign, appearing at numerous conferences attacking AI, including their therapeutic applications.

I can empathize with this unsettled feeling. Some of my friends have been using a text-based game called AI Dungeon an absurd amount. Some users have amassed hundreds or thousands of hours, even though the game is less than a year old. The game is run on machine-learned language models that take user input and the context of the conversation so far—the text interchanges of the play-through of the Dungeon—and spits out plot developments or player challenges. The model incorporates and mirrors the style of the user and his or her references in its outputs, the effect of which is a human-like “dungeon master” keeping the game interesting. Not an insignificant number of people have been using it for porn.

People’s obsession always felt weird to me. Partly it’s because I consider thousands of hours on a video or text game a waste of time. I quit video games cold turkey eight years ago after having spent an obscene amount of time playing them—something like 50 days of continuous time on League of Legends alone by fall 2012—so I have a strong association of time-wasting and video games. But that’s not why it feels weird and not instead crotchety at “kids these days”.

I think it’s weird because… don’t they know it’s not a real human? That the output is the result of a statistical model that reflects the representation and distribution of words in its training data? Once you know in principle what generated the text, what’s so interesting about the process of playing?

I generally try not to yuck others’ yums, so I don’t think much about AI Dungeon’s rabid fan base. But this weird, unsettled feeling got an update when thinking about AI-generated text in another domain, closer to Weizenbaum’s original purpose with ELIZA: therapy.

In the middle of the 99% Invisible’s episode you hear from the founder of a mental health chatbot, Woebot: “a chatbot guide who could take users through exercises based on Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, which helps people interrupt and reframe negative thought patterns. Woebot is not trying to pass the Turing test [a proposed test of a machine’s intelligence]. It’s very transparently non-human. It’s represented by a robot avatar and part of its personality is that it’s curious about human feelings.”

And in that moment, I thought Oh, I get it—I want to try Woebot. But isn’t Woebot just a statistical model, the output of which reflects the representation and distribution of words in its training data, i.e. not a human?

For my mental health, a chatbot that prompts me to reflect on my thoughts, is on the lookout for cognitive distortions, and sends me over the top feel-good GIFs is sufficient for the 90% of the time I have a spike of anxiety or a bad brain day. I just need a little guidance, even if it’s algorithmic or mechanical. The results of the process of CBT is what’s desirable, not necessarily human sympathy (although of course that’s desirable, too; I just get it elsewhere).

That tail of bad-brain-day distribution, though. Not sure that’s amenable to AI. (“Yet.” says VC twitter.)

Realizing that there is an positive epiphenomonal quality to artificial social interaction made me ease up a little bit towards AI Dungeon users, despite my initial intuition that it’s bad. I doubt any of them think there’s a human on the other side. Their enjoyment comes nonetheless. Should we disqualify or problematicize that joy simply because it doesn’t involve a human?

In pursuit of a more perfect union, let me live with my best friends.

Thoughts and practical advice on a gymnast’s core compentency.

My intuitions around therapy, emotional support, and chatbots.

An interview with Howard Baetjer

Max Efremov’s book review of Ross Douthat’s The Decadent Society

An interview with Tyson Edwards, YouTuber and All-Around Athlete

Folks I pay attention to.

A brief survey of Richard Schwartz’s Internal Family Systems (IFS) therapy.

An interview with Alexey Guzey, researcher and writer.

Intermittent fasting for a world stuck at home.

An interview with Luke O’Geil, gymnastics coach and gymnast strength trainer.

There’s strong, there’s really strong, and then there are gymnastics rings specialists.

In extremis, rising to the occasion with a ready mind.

Why on-the-job skills aren’t the only skills to keep sharp while job searching.

A search tool centralizing information pertaining to internationally sanctioned entities.

Thoughts on the (in)feasibility of any amendment to the US Constitution.

An interview with Scott Sumner, a monetary economist.

The details of a day in the life of a Lambda School student.

Progress in gymnastics is not only within reach of most people who can walk but, with proper coaching, can be the most rewarding sport you train for.

Scathingly funny.